To make the hooks, carvers shape two pieces of different wood into arms: yellow cedar is traditionally used for the upper arm because it’s buoyant and halibut are apparently attracted to the smell, while a heavier wood, such as Pacific yew, anchors the bottom. It’s an extraordinary example of traditional ecological knowledge being shared through an object, says study author Jonathan Malindine, a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. A recent study exploring how and why the dimensions of hooks have changed over time found that early hooks-primarily dating from 1860 to 1930-caught fish between nine and 45 kilograms, sparing the juveniles and the most prolific breeders, thus sustaining the species for future generations. Carvers use their hands to determine the angles and dimensions, which some believe allows them to target fish of different sizes. The practice of making halibut hooks has been handed down through the generations-literally. In fact, Rowan says he has just as much success with his wood hooks as he does his modern gear, in part because they’re technically ingenious, but also because they work on a spiritual level. The longline didn’t catch a single halibut. “See guys, I told you it was a catcher,” Rowan says.

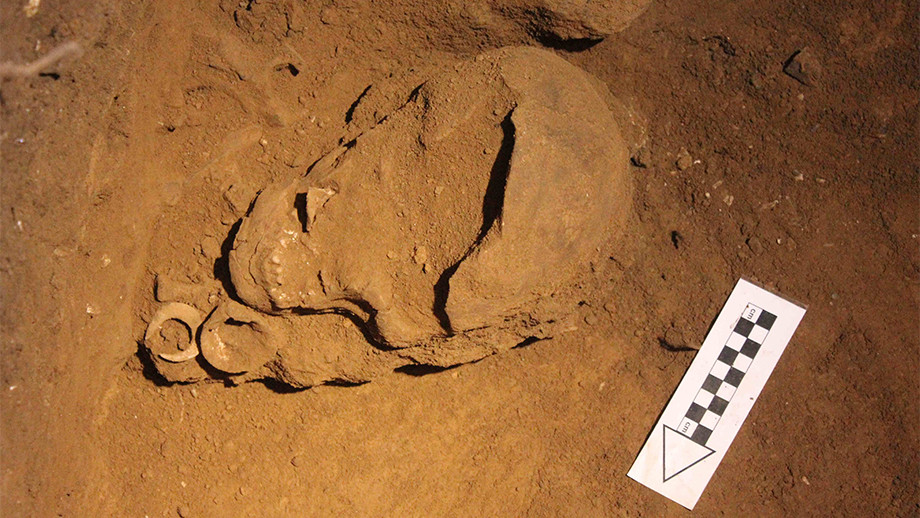

As they scan for what Rowan calls his “tattletale buoy,” it splashes to the surface and the tail starts slapping. “It’s a good feeling knowing that what you created has provided.”Īs Rowan returns to where he set his hook after his friends dropped their longline at a different spot, the beaver is nowhere to be seen. “There’s personal satisfaction in taking the same steps to make these hooks as my ancestors did and then being successful, too,” he says. For him, the connection to his culture and his land feeds his soul-and his family. Some days, Rowan drops a longline with 30 hooks, but the experience of sending down a wood hook is completely different. The figural element on the 28-centimeter-long hook depicts an unknown being eating, or spiritually connecting to, a halibut. McLean in 1882, and is now in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. This early halibut hook from the Tlingit tribe Xootsnoowú (fortress of brown bears) was collected in Angoon, Alaska, by John J.

Ancient fish hooks how to#

But now, Rowan and other carvers are trying to revive the ancient tradition by teaching people how to make and use the hooks for what they were intended, and helping them reconnect with their culture in the process. In fact, many carvers started making hooks specifically to hang on the wall rather than above the seafloor. Over time, wood hooks were replaced with off-the-shelf fishing equipment with no assembly, or artistic aptitude, required.Īs the hooks came out of the water, they found new homes on land as art pieces and collectors’ items. In his community of about 800, Rowan can count on one hand the people who practice this traditional technique. Indigenous peoples of the northwest coast of North America have been hauling in halibut on what are known colloquially as “wood hooks” for centuries, but very few fishermen use them today. As Rowan surveys the scene, he pictures his ancestors setting hooks in the same spot, reciting the same words of encouragement, and, hopefully, having the same good luck. The wooden buoy bobbing in the water will let him know if he’s right-also carved to look like a beaver, the tail will start slapping the surface if a struggle is underway beneath the waves. “That’s a catcher right there,” Rowan had said, selecting the hook from his collection of about eight for today’s expedition. The previous morning, the hook had fallen off a cup hook in the ceiling of his workshop and landed between him and his friends as they were having coffee and discussing where to fish. Rowan, a master carver, is acting on an omen. From his skiff, the tribal leader, who is joined by two friends, watches the V-shaped hook about as long as his forearm slowly sink and hopes the imagery he carved on the seafloor-facing arm-a beaver perched on a chewed stick-entices a halibut. Jonathan Rowan lowers his handmade wooden halibut hook into the tranquil early-morning water off Klawock, Alaska, and urges it to go down and fight: “ Weidei yei jindagut,” he says in the Tlingit language. This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)